SINCE THIS STORY IS SET IN KENYA, let’s start by learning a few words in Swahili.

Uso kupooza upande mmoja means ‘one side of the face may droop or become numb’.

Pooza mkono/mguu is Swahili for ‘weakness on one side affecting the arm or leg’.

Eleza (ugumu wa-) refers to ‘slurred or unclear speech’.

Simu upesi means ‘call for help fast’.

Together, they make up the acronym UPESI, the Swahili version of FAST, created to increase stroke awareness in East Africa where Swahili is spoken by over 200 million people.

Spearheading this project, which was carried out by two stroke physicians, a nurse and two professional translators, was Dr Peter Waweru, a neurosurgeon based at Kenyatta University Teaching, Referral and Research Hospital (KUTRRH) in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi. Subsequently, an even bigger team including speech therapists was assembled to undertake the translation and cultural adaptation of the world’s most widely used stroke severity scale, the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).

“We’re quite excited about it,” Dr Waweru says, adding that the Glasgow Coma Scale was previously used to evaluate stroke patients. “It wasn’t really the correct tool and it prevented us from participating in some international trials where NIHSS was the standard. Now that the NIHSS has been translated into Swahili, we are using it much more often and we are disseminating it and letting people know about it so that it can be translated into improved stroke outcomes.”

Dr Waweru is no linguaphile; his interest in translation doesn’t stem from a special appreciation for words. Rather, the point is that translation removes language barriers, and removing language barriers eliminates access barriers and promotes equity. And health equity is something Dr Waweru does care deeply about.

It’s one of the reasons why he works in a public hospital, why he is cofounder of Nairobi-based Pan-African Center for Health Equity (PACHE), why, as a neurosurgeon, he immerses himself in “vessels and stroke”, and why his research interests are split between hemorrhagic stroke (which disproportionately affects a population plagued by underdiagnosed and poorly controlled hypertension), and developing stroke systems of care in low-resource settings.

There is however another reason, and it has to do with love.

‘All of a sudden she was gone’

Let’s go back 20 years to where Peter Waweru has just completed his secondary education at Thika High School, a boys-only boarding school located in Kiambu County about 42 km northeast of Nairobi, and decides to study medicine after all.

“I think I always wanted to go into medicine from when I was in primary school,” he says. “At some point I detoured to really wanting to become an electrical engineer but after getting my results and talking it over with my dad, I went back to my first love of medicine.”

Two years into his studies at Kenya’s Moi University, a personal tragedy occurred when Peter lost his grandmother to stroke.

“This was my maternal grandmother, and we really, really loved her, because she was our support system,” he says. “And all of a sudden she was gone.”

Despite being admitted to a secondary referral hospital, the family matriach hadn’t received life-saving care.

“She didn’t even get a CT scan, just a saline drip, and eventually she was discharged home. She was not in a good state, and she didn’t stay for long. I think they were just discharging her to go die at home.”

His resulting interest in stroke, already a matter of the heart, saw him specialize in neurosurgery and simultaneously study towards a master’s in stroke medicine at Austria’s Danube University Krems, an eye-opener from which he “never really looked back. I knew this was the direction I was going to pursue. So I was never interested in brain tumours and all those other things anymore: it has always been about vessels and stroke.”

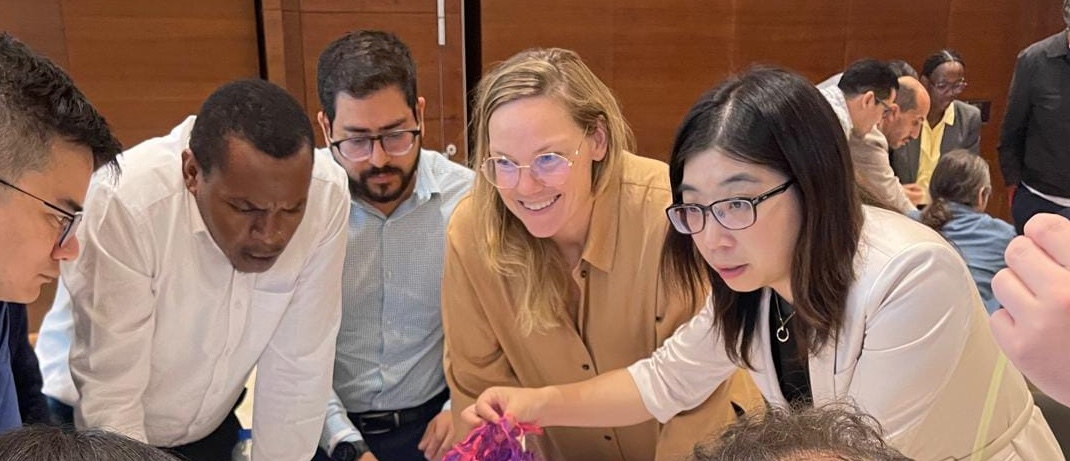

For a neurosurgeon with a passion for stroke, the European diploma in Neurointervention offered by Oxford University was a logical next step, and in 2022, the indefatigable student further embarked on the WSO Future Stroke Leaders program, which, with its emphasis on quality stroke care implementation, accelerated stroke care transformation at KUTRRH.

KU sets the bar

KU, as the hospital is affectionately known, is a highly specialized modern, sophisticated public healthcare facility with state-of-the-art technology and advanced medical capabilities. When Dr Waweru arrived here five years ago, after working in some of Nairobi’s top private and faith-based healthcare settings, the hospital was a Covid centre.

“We couldn’t do a lot of work in terms of stroke, because we were primarily taking care of Covid patients,” he recalls, “although we did get a very intriguing window on how Covid affected stroke outcomes and stroke presentations.”

They even participated in an international study on the impact of Covid-19 on global patterns of stroke, but the truth was back then KU had no stroke program at all. “There was no protocol for stroke. There were no beds, there was no stroke unit.”

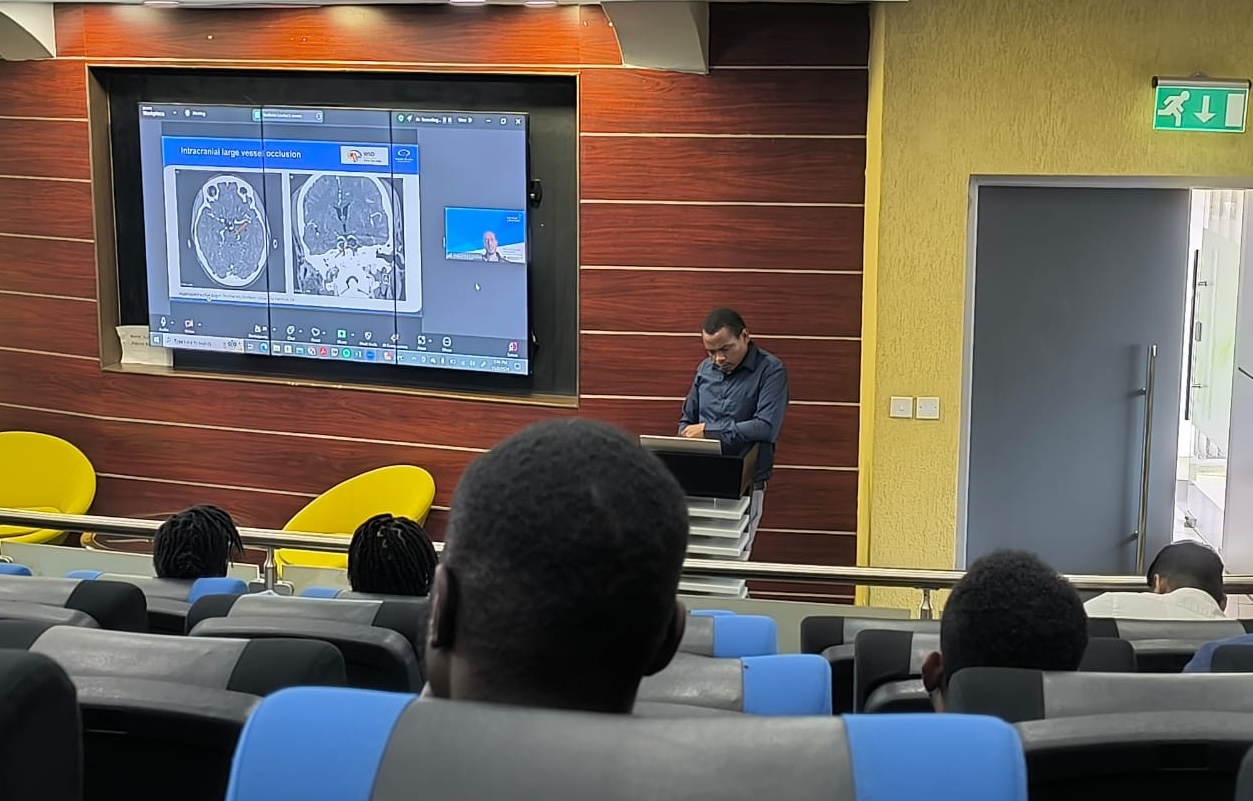

In the past two years, however, KU has become a stroke-ready comprehensive centre, with the capacity to treat stroke with intravenous thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy. The hospital has two CT scanners and two MRIs and a dedicated neurologist with an interest in stroke. There is a stroke program, a stroke protocol and well-attended stroke rounds on Tuesdays. Part of the neurology ward has been set aside for stroke patients, and an implementation committee formed to operationalize the region’s first stroke unit located in a public hospital. Not for the first time, KU is setting the bar.

A fight for equity

Angels consultant Annie Kariuki, looking back on the first year of the Angels Initiative in East Africa, is proud of the strides KU has made and grateful for a stroke champion whose commitment to better outcomes for stroke patients goes deeper and wider than his own hospital.

Across the country, there’s a great deal to be done. “There are no structured systems for stroke care,” Dr Waweru says. “From the prehospital phase – stroke awareness, knowledge of symptoms and the appropriate emergency response – to the hyper acute phase, the acute phase, rehabilitation, secondary prevention . . . throughout the stroke continuum, there are a lot of gaps. But I’d say the biggest problem is twofold. Number one, awareness and appropriate emergency response in the community. And number two, having hospitals that are able and ready to take care of these patients.”

The problem becomes more complex, the greater the distance from cities.

“A recent study showed that two-thirds of our stroke patients are in the rural areas where there are hardly any specialists, so a lot of our stroke patients end up in the hands of clinical officers who generally have very limited knowledge on stroke.”

Educating primary care physicians – a project of the fledgling Kenya Stroke Society – will hopefully ensure more patients reach tertiary hospitals on time.

These challenges are the reason a neurosurgeon with the world at his feet ended up in the public healthcare sector, and why he stays there.

“The whole concept of health equity has been something that drives me,” Dr Waweru says. “I see it a lot. I see patients who would have been saved if they’d had the money for specialist treatment, but because they cannot afford it, they end up dying.

“When you think about it, it’s exactly what happened to my grandmother. If we’d had enough money to take her to a hospital where she could get the care she needed, who knows, she might still be here. And so this inequity is probably what has driven me.

“I have worked in all three kinds of hospitals in Kenya. I have worked in mission hospitals and in private hospitals and after all I have seen, I know that if we all end up in the private sector where most of our specialists are, then these patients won’t get the care they need.”

Strength in networks

The Kenya Stroke Society (KSS), which will be formally launched at November’s African Stroke Organization Congress (ASOC) in Nairobi, is an advocacy platform to lobby health authorities about policy changes that will result in better care for all patients.

“It’s the newest kid in the block,” Dr Waweru says. “The idea started last year when together with Angels we sat down and realized one of the biggest challenges was how we advocate for better care. There are scattered professionals here in Nairobi, a few in Mombasa, a few in Kisumu who have a passion for stroke, but it’s hard to make progress unless we come together.”

Dr Waweru’s own journey to leadership has demonstrated the principle of strength in numbers and networks.

“I really got into stroke leadership through the WSO’s Future Leaders program, but I would never have known about this program if I hadn’t done the courses I did with the ESO,” he says. “So it’s all tied together – the ASO, ESO, the European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT), and the WSO – it’s a network of organizations that have all contributed significantly to our stroke journey.”

If the new society succeeds in its ambitions its impact will be felt across the continent. Dr Waweru says, “We’re trying to get together all the leaders who have graduated from the Future Leaders program that come from Africa. We’re calling this the WSO Future Leaders Program African Task Force.” Such a task force would facilitate participation in international studies and add momentum to the transformation of stroke care in Africa.

“For us in Kenya, in stroke, we are quite young, so we have to learn from these others,” Dr Waweru says.

ASOC in November offers exciting opportunities, and in addition to taking part in the planning and contributing abstracts and speakers, the KSS is also coordinating a stroke run to raise public awareness. Dr Waweru’s excitement about this event is understandable because running in Kenya is not like running in other countries.

A global powerhouse in track and field, Kenyan runners have consistently dominated events ranging from the 800 meters to the marathon. At the World Athletics Championships in Tokyo this past September, they finished top in Africa and second in the world. So it’s fitting that double world champ and former Olympian Bernard Lagat will be among those lining up at the start of November’s stroke run. It’s a potentially electrifying way of spreading the word about stroke.

“It’s quite apt for us because when it comes to running we’re talking about time,” Dr Waweru says. “We’re talking about ‘fast’. We are talking about upesi. So it’s quite, quite exciting for us now.”